Worldwide Terrorism & Crime Against Humanity Index

Should Japan Militarize?

Japan Considers Revising Constitutional Constraints on Military Defense Forces

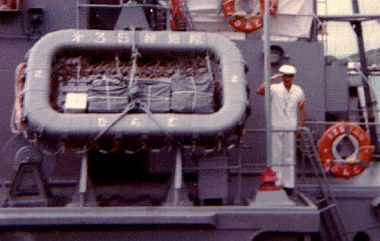

Quadruplets: Four Armed Japanese Minesweepers

A US Naval vessel sits across the pier to the left at White Beach Okinawa

(Bob Price Photo 1975)

Artical by Global Intelligence/Stratfor.Com 2001

Photos by Bob Price

According to a report in Japan's Kyodo News Service, at a joint meeting on April 22, the Foreign Affairs and Defense committees of Japan's ruling Liberal Democratic Party approved a draft revision to the country's Self- Defense Forces Law which would allow greater latitude in the use of force by Japan's armed forces.

A previous draft of the bill would have allowed Japanese forces to use only minimal force if their lives were endangered while performing search and rescue or maritime inspection duties. The new draft of the bill states that Japanese forces may use weapons "to the extent judged reasonably necessary."

Furthermore, Kyodo News Service reports that the draft bill allows Japanese forces to use weapons "when they evacuate overseas Japanese nationals, at places where planes and ships are located, and along the routes they take to escort Japanese to planes or ships." Prime Minister Hashimoto's cabinet is expected to approve the draft bill on April 28, and then pass it on to the Japanese Diet for final approval.

Japan was banned by Article 9 of their US-influenced post-war constitution from using their military in anything but a self-defense role. Throughout the Cold War, this provision served the country well, as the United States carried the economic burden of defending Japanese interests in return for bases from which to confront the Soviet Pacific Fleet.

Once We Would Have Been Enemies; Now We Can Be Friends?

Japanese Sailor returns a Salute from the deck of his minesweeper

(Bob Price Photo -1975)

Since the end of the Cold War, however, Japan has been engaged in an internal debate over whether the country's significant role in international economic affairs demanded commensurate participation in the politico-military realm.

This debate received added impetus during the 1990-91 Gulf War, and during the 1996-97 hostage crisis at the Japanese embassy in Peru. An April 21 article in the Yomiuri Shimbun bemoaned the fact that Japan's claims on the disputed Senkaku, Takeshima, and Kurile islands were weakened by the constitutional constraints that prevented Japan from projecting an effective military presence in the region.

With the Asian financial meltdown and, more to the point, Washington's tepid response, Japan has been confronted by the fact that they are largely on their own. The United States' close cooperation with Japan on economic and military matters throughout the Cold War was driven more by the need to contain the Soviets than by US love of Toyotas.

As US and Japanese interests have become unlinked, Japan has pursued a foreign policy more at odds with that of the United States.

Japan's State Secretary for Foreign Affairs, Masahiko Komura, is currently on a four-day visit to Tehran, where he has touted Iran's "key role in regional stability."

Komura asserted that Japan seeks increased political and economic ties with Iran. Japan is also pursuing the conclusion of a final peace treaty with Russia, and is eagerly pursuing a variety of energy and development projects throughout Russia, at a time when Russian and American interests are once again beginning to clash in the Middle East and Central Asia.

The Japanese Flag Still Flys Over The Decks of Warships

Japan is stepping away from its former symbiotic relationship with the United States, and part of that step is the easing of restrictions on Japanese force projection. As Japan vies with China to become the dominant regional power, we expect this initial revision of the Self-Defense Forces Law to be followed soon by more substantial changes.

Source: www.stratfor.com

Should Japan Defend itself?

Unlike nearly everyone in Japan and the rest of Asia, Americans want Japan to spend more on its military, thinking that will equalize economic competition.

It won't...

by James Fallows

From The Atlantic Monthly Online

AMERICA'S biggest delusion about Japan is that the "free ride" on defense that we give Japan is the key to the two countries' problems. If we can only make the Japanese pay for their own protection, many Americans feel, our economic difficulties will work themselves out.

Last fall, before he was nominated as Secretary of Defense, John Tower told a Japanese interviewer what he later said during his confirmation hearings: that Japan should change its Constitution if that's what it would take to start spending more on defense.

In its past session the U.S. Congress passed a resolution demanding that Japan spend three percent of its gross national product on defense, as opposed to the roughly one percent it spends now (and to the seven percent the United States spends). "Our European partners spend about three percent," an aide to Representative Duncan Hunter, of California, who sponsored the resolution, said early this year. "It's entirely reasonable to expect Japan to do the same."

Last year Representative Patricia Schroeder, of Colorado, recommended a "defense protection fee" on all Japanese imports, to make the connection between our protection and their prosperity as bluntly explicit as it can be: for each car the Japanese bring into America, they would have to cover some of the cost of the American ships and planes that guard Japan. Otherwise, why should the United States, with its huge deficits, keep paying to protect a country whose surpluses pile up by the day?

Behind these proposals, and the broader public grumbling about Japan's "free ride," is the idea that America's economy has been hobbled by defense spending, so in all fairness Japan's should be hobbled too. Or, to put it more pleasantly, that Japan should take up some of America's burden, so that the two economies can compete on a fairer and more equal basis. However it may be phrased, the essential idea is that Japan has been imposing on our good will for just about long enough. Who won the war, anyway? If the Japanese don t back off from their aggressive trading practices, we will have to teach them a lesson by withdrawing some of the military protection we magnanimously provide.

I think this concept has things exactly the wrong way around. The military relationship between Japan and America, "free ride" and all, is much better for each party than any alternative I've heard suggested so far. The division of labor is complicated and obviously unequal -- even if Japan is paying more and more of the cost of defending its own home territory, it has nothing like America's worldwide military costs. Still, it sounds easier to correct the imbalance, by "making" Japan pay its way, than it turns out to be when you look at the details. We can do ourselves a favor if we concentrate on our real disagreements with Japan, about trade policy, and forget about the "free ride."

Before getting into the details, let's step back to consider how much damage the defense imbalance does, and how the United States got itself in this bind. Of course the difference between the Japanese and American defense budgets is enormous, and is a significant economic problem for the United States.

Some Japanese officials have recently been trying to convince people that the imbalance is not as large as it seems. After all, they point out, Japan is now overtaking Britain and has the third-largest military budget in the world, which sounds about right for a country with the world's second-largest economy. "Third-largest," however, is completely misleading, because it reflects little more than the enormous increase in the value of the yen.

In 1985 Japan's defense budget was the eighth largest in the world, comparable to those of such questionable powers as Italy and Poland. Since then the budget as measured in yen has gone up steadily but modestly, in pace with the Japanese economy as a whole -- from about 3.1 trillion yen in 1985 to about 3.7 trillion in 1988. As measured in dollars, however, the budget zoomed upward by more than 200 percent in those same three years. Because international budget comparisons are still made in dollars, it's the exchange rate, rather than a real defense buildup, that has propelled Japan toward the top of the charts. Even at these inflated dollar-yen rates, Japan's defense spending is about one tenth of America's, roughly $30 billion a year versus roughly $300 billion.

If we use NATO's system of measuring defense budgets, which includes (as Japan's does not) military pensions and other costs in the total, Japan's spending comes to about 1.7 percent of its GNP. This is still much less than that of any major Western country. In terms of the burden the country imposes on itself, Japan has at most the twentieth-largest military budget in the world.

U.S. industry is handicapped in a further way, relative to Japan's. When American military interests have collided with the interests of American companies, U.S. policy has favored the military. It is more convenient for American commanders, for example, if allied nations all use similar equipment. Therefore the Pentagon has willingly licensed advanced weapons technology to NATO countries, Korea, and Japan, so that they can build compatible equipment for themselves. The F-15s that are the backbone of Japan's air force are manufactured in Japan, under license from McDonnell Douglas. This approach, of course, erodes America's technical lead and in many cases has spawned direct competition in the arms business.

Japan's bias has been just the opposite of America's. Its military commanders would be much better off if Japan imported its weapons, rather than building them domestically in small, costly production runs. But, unlike the United States, Japan can put commercial interests over military ones, so it spends 90 percent of its procurement money at home. Last year Japan faced a black-and-white choice between military efficiency and promotion of its own industry, when it selected a new fighter plane for its air force. Every factor except industrial promotion pointed toward one decision: buying the F-16 fighter plane from the United States. The F-16 was available immediately, it was battle-tested, and it was comparatively cheap. This is one case in which every normal market standard favored the U.S.-made product.

And yet Japan attempted for as long as possible to design and build an entirely new airplane, all its own, as an entry to one of the few industries in which it is still behind. The U.S. government was indignant about these plans. Japan eventually threw us a sop, by agreeing to accept the blueprints and technical specifications for the F-16, and, after modifying the wings and radar and certain other parts, to build the new "FSX" planes in Japan, with some American subcontracting. Japan's military will suffer from this deal. The planes won't be ready until the middle of the next decade, and they will cost about twice as much as F-16s. But Japanese industry will, for the first time, have the experience of putting together a modern plane from drawing-board to final assembly.

THE FSX deal is, as The New York Times said in an uncharacteristically sharp-tongued editorial, "one-sided and unfair." But does it, or any other part of the military-spending imbalance, mean that the United Suites can eliminate its burden by changing its military relationship with Japan? Unfortunately, it does not. In principle, Japan could solve the "free ride" problem in either of two ways. It could spend much more on its own defense, or it could pay more of America's costs -- essentially hiring the United States for Pacific defense. The United States will have a very hard time persuading Japan to do either.

The first approach -- putting pressure on Japan to expand its own military -- would be wildly unpopular in Japan and everywhere else in Asia. Japan and its neighbors remember the Second World War in different ways, but the memory leaves all of them hostile to the idea of a strongly re-armed Japan.

It is hard for most Americans to imagine how deep is the fear of Japanese rearmament that spreads across the rest of Asia -- and that persists in Japan as well. Someone who had never opened a history book might look at today's Japan and conclude that the fear was completely absurd. This is about as civilian-looking and nonmilitarized a society as you will find. True, many parts of Japanese life do seem regimented and quasi-military. But these are the civilian parts: the industries, where workers do calisthenics beneath snapping company flags, with martial music booming through the air; the schools, where boys wear shorts all through the winter to show that they are tough. The fierceness and esprit in the military itself cannot compare. There are some 250,000 soldiers in the jieitai (literally, "self-defense force," rather than "army"), but they're practically invisible. Soldiers refuse to wear their uniforms in public; they commute in civilian clothes and change once they get to work. In any case, the uniforms seem bus-conductor-like and deliberately nonmartial, especially by comparison with the severe Prussian-style outfits worn by high school students.

Japan's equivalent of the Pentagon is situated near the Roppongi stop on Tokyo's subway, in a chic tourist and nightclub district. If you ride the Washington, D.C., Metro to the Pentagon stop, you will see uniformed soldiers by the hundreds; I have never seen a uniform in the Roppongi crowds. The Defense Agency proudly releases polls showing that Japanese people have a favorable impression of the military. But according to these same polls, 77 percent of the Japanese public think that the military's most valuable function has been to clean up after typhoons and provide other forms of disaster relief.

In today's Japan of Sony and Toyota, joining the military is a very unfashionable career move and the jieitai has a harder and harder time attracting recruits. It is about 30,000 soldiers below the level authorized by Japanese policy, and there are relatively few people in the reserves.

The army would be in terrible trouble if it were not for the southern island of Kyushu, which contains only about an eighth of Japan's people but seems (judging by the soldiers I've met) to produce most of its recruits. In Kyushu, which has a long history of famous warrior clans, I have heard families say that they wanted their sons to grow up to be soldiers or sailors, but not anywhere else. Three years ago I interviewed cadets at the National Defense Academy, in Yokosuka, where future officers are trained. I asked them why they had chosen careers in the military. The ones who weren't from Kyushu often gave answers like "failed my exams for Todai" (the hallowed University of Tokyo) and "wanted a free education."

There is an air of unseriousness about Japan's military undertakings, which is especially noticeable by comparison with the deadly earnestness of everything else. Soldiers are officially just another kind of government employee: there is no court-martial system, no penalty for refusing to join the military after getting a free education at the academy, no system of emergency laws empowering the military to do what it must for national security.

At the Japanese air-force base in Okinawa an officer was giving me a lecture about the supersensitive "hot scramble hangars," where F-4 fighters wait to intercept the Soviet planes that fly close to Japanese air space every two or three days. Just as he finished warning me not to get too close or take any pictures, an All Nippon Airways jumbo jet taxied by, full of vacationers gawking out the windows at the hangars. At Okinawa, as at the other major Japanese air-force base -- Chitose, on the northern island of Hokkaido -- the air force has to share runway space with, and be bossed around by, the civilian airlines.

Political "debates" about defense usually begin and end with statistics.

"Discussions in the Diet are always and only about the 'one percent limit,'' says Motoo Shiina, one of the rare politicians known as an expert on defense. "You can sulk about one percent for an hour, pro or con, but you shouldn't talk about anything else."

THERE are many explanations for Japan's nonchalance about the military. The most obvious is Article IX of its postwar Constitution, drafted in English by General Douglas MacArthur's occupation experts and translated into stilted Japanese. Contrary to general belief in the United States, this "Peace Constitution" does not set a ceiling on Japanese defense spending. The "limit" of one percent was in fact merely a policy guideline adopted "for the time being" by the Cabinet of Prime Minister Takeo Miki in 1976.

Eleven years later, under Yasuhiro Nakasone, Japan broke the limit when its spending reached 1.004 percent of GNP. The change was more significant than the tiny violation might suggest. For one thing, Nakasone's government presented a Midterm Defense Program, which outlined the new equipment the military would buy from 1986 to 1990. Such plans had existed before, but this was the first one backed up by real money.

The government committed 18 trillion yen (about $150 billion at current rates) to be spent on the military over five years, at a time when most domestic spending was being reduced. This should be enough to buy all the weapons listed in the plan, and enough to keep defense spending slightly above one percent of GNP. Also, this move was an attempt to move Japanese defense discussions away from the one-percent obsession, so that budgets could be based on what the military actually needed. In principle, the government now sets budgets without worrying about the limit, but in practice, anything above one percent creates intense political resistance in Japan.

Rather than limiting defense spending, Article IX of the Constitution prohibits it altogether -- or so it seems, if the original English version is taken at face value. "Land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained," it says, because Japan "forever renounce[s]" resorting to armed force as a sovereign right. Japan has worked its way toward its current sizable military force through a series of judicial and political "reinterpretations" of the Constitution. The crucial legal concept has been the idea that no nation can renounce the right to defend itself against attack, much as no individual is allowed to sell himself into slavery.

Until 1950 MacArthur's policy discouraged Japan from developing an armed force of any sort. But as American soldiers were called away to Korea, MacArthur ordered Japan to establish a National Police Reserve, comprising some 75,000 men, which later evolved into the Ground Self-Defense Force.

Some Japanese intellectuals contend that the half-serious, bastard nature of the jieitai is spiritually bad for the country. Shuichi Kato, a renowned leftist literary critic, was staunchly against the Vietnam War and is always alert for signs of renascent militarism in Japan. But when I first met him, in 1986, he said, "And yet you cannot deny that Americans were risking their lives in Vietnam for something they believed. Japan is not asked to do that now." Hideaki Kase, from the opposite end of Japan's political spectrum, says essentially the same thing. Kase, best known for his veneration of Japan's imperial family, says, "We have been playing a very profitable game of posing as unconscientious objectors. We base our defense policy not on preparation against a hostile threat from the Russians but on the need to placate the Americans." In contrast, Masataka Kosaka, a professor at Kyoto University who is known as one of Japan's few "defense intellectuals," says that Japan's military has a spiritual advantage over those of most other countries. In the age of nuclear weapons, he says, fewer and fewer armies from major countries will actually fight, and yet somehow they must maintain morale. Japan's army has lived with this predicament for more than thirty years, he says, and it will set the model for armies of the twenty-first century.

Whether the hazy legality of the jieitai is good or bad for Japan, it indicates Japan's lack of interest in expanding its military. Public-opinion polls in Japan show overwhelming resistance to increases in defense spending. (In a recent poll 80 percent of respondents favored keeping spending at or below the current level of one percent.) Moreover, Japan's peculiar way of remembering the Second World War intensifies the resistance to re-arming. Japan is not exactly guilt-ridden about its role in the war -- the Peace Memorial Museum, in Hiroshima, for instance, begins its historical narrative with the American firebombing of Tokyo in the spring of 1945, with no mention of any preceding unpleasantness. But Japan seems unanimously and permanently convinced that the war led to catastrophe for the country. Moreover, the prevalent view in Japan is that the war was caused by a clique of semi-crazed militarists, who seized control of the country and forced everyone else into what was clearly a suicidal undertaking. This attitude is tremendously irritating to Chinese or Koreans who are looking for signs of personal contrition from the Japanese, but it actually makes for a very durable kind of anti-militarism -- one based on self-interest.

"The war created lasting suspicion of the military, but not because we made other people suffer," Shuichi Kato says. "The memory of the war is that we suffered so much." Most mature Japanese can remember the utter ruin of the postwar years; they blame General Tojo and his cronies for it, and they don't want the military to have another chance.

In the rest of Asia there is more of an edge to memories of Japan's wartime role. As I've listened to officials -- in China, especially -- warn about the danger of a militarized Japan, I've suspected that their fears were partly put on for effect. Japan's war record is one of its few vulnerabilities, and these warnings are a way to get America's attention. Still, I've heard the warnings in every neighboring country (except Burma, where the Japanese are generally viewed as liberators who kicked out the British), and for the most part the apprehension seems sincere.

Throughout Asia the least popular American trend is the apparent enthusiasm for big Japanese defense spending. Lee Kuan Yew, the Prime Minister of Singapore, has warned for years about the dangers of Japanese re-armament, although recently he has started saying that a bigger Japanese military is inevitable and that the crucial thing is for it to keep working as a junior partner to the Americans. "As long as our military seems firmly under the guidance of the Americans, the rest of Asia will not worry too much," says Masashi Nishihara, a professor of international relations at the National Defense Academy. "If we ever went off independently, everyone would be afraid."

In short, deeply felt emotions in Japan and throughout the rest of Asia put a low ceiling on Japan's potential military spending. Long before the defense budget increased enough to hobble the Japanese economy, it would have provoked some political reaction from China and South Korea, and probably the Soviet Union as well. (Exactly what kind of reaction is impossible to say, but it certainly couldn't leave northeast Asia as free of major conflict as it has been since the Korean Wan) But there is a further limit on Japan's spending: it is hard to see what Japan could spend a lot of extra money for.

THE question of "enough" is hard for any country considering its national defense to resolve, but it is particularly baffling for Japan's military. In theory, Japan could cut its military budget to zero and still feel more or less secure, relying on the U.S. nuclear deterrent and on the knowledge that no one has dared invade the home islands of Japan since the time of Kublai Khan. Or Japan could equally well decide that its national-security interests extend to every ship that brings in raw materials or carries out exports; in that case, Japan would need to build the world's biggest navy to defend itself completely.

In practice, Japan has defined "enough" by taking on, one after another, jobs that America has handed it during the past two decades. Its military now has three main missions: to be ready to defend the northern island of Hokkaido against a Russian assault; to be able to seal up the crucial straits of Soya, Tsugaru, and Tsushima, through which the Soviet navy must pass to get from Vladivostok to the open sea, and in general to erect air and sea defenses that will keep the Soviet military bottled up in Siberia in time of war; and to patrol the commercial shipping lanes leading southward from Japan toward the Philippines and the Straits of Malacca. In principle, this means that Japan is now completely responsible for defending itself with conventional weapons against a conventional attack. The U.S. military's part of the bargain is to provide a nuclear deterrent and, through the destroyers and aircraft carriers of the Seventh Fleet, to do the kind of long-range "power projection" that no Asians want the Japanese to undertake.

Japan's assignments are somewhat vague and open-ended. For instance, the responsibility for defending sea lanes, since 1981 mainly against Soviet submarines, has included a thousand-mile stretch. But exactly how the Japanese will divide this labor with the United States, and how much sea power they will deploy, is unclear. What is clear is that Japan is well on its way to having a big enough army to do its jobs, even at its current "free ride" budget levels. Under the current Midterm Defense Program, Japan is supposed to increase its force of F-15 fighters to 700, and modernize its 100 F-4s. It will replace its older Nike anti-aircraft missiles with Patriot missiles, increase the number of its P-3C anti-submarine aircraft from 50 to 100, and build 10 new destroyer-type surface ships. Even during the Reagan-era military buildup the U.S. inventory of most major weapons shrank, because the cost of weapons rose faster than the budget. For the next few years Japan will be the only major military power in the world that is buying new weapons and at the same time expanding the size of its force. Japanese military officials often say that their forces are small and humble, but most other defense authorities I've interviewed here say that Japan has no urgent need for new hardware which implementing the Midterm Defense Program won't meet.

Japan's military still has some glaring weaknesses. According to U.S. observers, it has never laid in adequate supplies of ammunition, fuel, or spare parts. "They better hope the first volley holds off the Russians," an American military officer says. "They've barely got one reload of missiles." Also, the three branches of the Japanese military are even more uncoordinated and prone to backbiting than the branches of America's are. When a Japan Air Lines jumbo jet crashed in the mountains outside Tokyo in 1985, the rescuers reached the site twelve hours late, in part because the air force, the army, various police forces, and other government agencies were trying to decide who should do what in the rescue effort. The survivors reported that several other people were alive after the crash but died during the night, while the branches of the jieitai spun their wheels. "This delay cost several lives," says Masataka Kosaka, of Kyoto University. "In wartime such behavior would be catastrophic."

Despite such problems, many serious military analysts conclude that Japan is smoothly moving toward "enough." Shunji Taoka, a veteran defense writer for Japan's most prestigious newspaper, the Asahi Shimbun, has prepared a dense analysis showing that the Soviet Union lacks the troop carriers and transport planes to overwhelm Japanese defenses during a surprise attack on Hokkaido. Moreover, he says, the Soviet Far Eastern fleet is sure to weaken over the next decade, because its ships are aging faster than they are being replaced. "Japan exercises the responsibility for its own non-nuclear defense," Michael Armacost told me shortly before he was nominated to succeed Mike Mansfield as the U.S. ambassador to Japan. "Japan already possesses substantially more destroyers than we deploy in the Seventh Fleet; it has a larger force of surveillance aircraft than we maintain in the Pacific; it has nearly as many fighter aircraft defending its territory as we have defending the continental United States. This is a significant force and provides solid protection."

Japan can undoubtedly go much further toward having "enough." One executive of an American defense contractor, based in Tokyo, says that he has a vision of "porcupine Japan," bristling with cruise missiles and electronic air-defense systems that protect it against attack without threatening any of its neighbors. Japan can also, and will, increase its foreign-aid payments, which is a subject for another time. But -- to get back to the main point -- nothing in Japan's internal politics, its relations with its neighbors, or its military plans will make it spend enough money to weaken its economy as that of the United States is now weakened.

THAT leaves the other possibility -- forcing Japan to shoulder some of America's military costs. Americans imagine that they have tremendous leverage against Japan on this point: Pay up or we'll leave you exposed. This, however, would be an undignified position for America to take. Worse, it wouldn't work.

As long as the United States remains a military power in the Pacific, it needs Japan's cooperation at least as much as Japan needs U.S. protection. I mean cooperation not in some abstract sense but as a practical matter of where the United States can station its troops and dock its ships. In West Germany and South Korea, American troops are stationed largely near the front, to guarantee that they'd be involved if fighting began. But there is not a single United States soldier in Hokkaido, the most likely invasion site in Japan (to the extent that any site is likely).

Of the 55,000 U.S. soldiers and sailors in Japan, two thirds are based in Okinawa, a thousand miles southwest of Tokyo, where they are mainly a swing force to be used in Korea or elsewhere in Asia. The other major concentrations include a U.S. Air Force base in Misawa, in northern Japan, the closest of all American bases to the imposing Soviet military centers on Sakhalin Island; the naval base at Yokosuka, a crucial dry-dock and refitting site for the U.S. Seventh Fleet; Army facilities at Zama and a naval air installation at Atsugi, both near Tokyo; and a Marine air base at Iwakuni, near Hiroshima. "We are not being honest...when we talk as though American overseas military deployments have been essentially altruistic -- not for ourselves but for our allies," Martin Weinstein, of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, in Washington, D.C., said in congressional testimony last fall.

The real problem for America is not that it has to keep bases in Japan but that it might lose them, according to Dennis J. Doolin, a former Pentagon official who specialized in U.S.-Japanese relations. "We are...in a logistically ideal strategic posture in Northeast Asia," Doolin has written, "and we had better learn to appreciate this fact and stop complaining....Japan's contribution is enormous, unique, irreplaceable, and invaluable."

Moreover, Japan already bears more of the cost of the American troops stationed on its territory than does any other allied country. Its program of "host-country support" covers about 40 percent of the roughly $6 billion cost of keeping American soldiers there, and the Japanese-paid proportion is increasing every year. (Japan says that under its Constitution and its-Status of Forces Agreement with the United States it can't pay the salaries of American soldiers or direct military operating costs, like those for fuel and supplies. It is gradually taking over most other costs.) The presence of foreign troops creates inevitable irritations: think how Americans would feel if, instead of "buying up America" in some theoretical way, the Japanese had soldiers in Chicago and aircraft carriers cruising through the Golden Gate. The Japanese government goes out of its way to deflect resentment of the United States. For instance, when some trees in a diminutive forest were cut down last year to make way for new U.S. military housing, creating a huge controversy, the Defense Agency made clear that Japan's government, not America's, had authorized the project. Just about everything Japan can do for the American military in Japan it is already doing or getting ready to do.

The one big exception to Japan's generally cooperative approach is -- surprise -- its weapons-buying policy. Each time Japan insists on industrial-strategy projects like the FSX, -- it feeds all the worst suspicions about its sense of balance and fair play. But these disputes should be thought of the way the Japanese think of them -- as trade disputes, not military ones. Japan could ease trade frictions, while getting twice as many weapons for its money, if it bought planes and missiles directly from the United States, rather than building them at home. But this will be one of the last areas Japan opens to imports. Japanese officials are quite candid about their determination to develop their own aircraft industry and in general to use military contracts for industrial development. They are less candid about exports of military equipment, which now occur on a small scale and could increase, because the main barrier to them is not Japan's Constitution but its fear of international reaction. Last summer the Tokyo office of Warburg Securities released an influential report on Japan's nascent arms industries, including strong "buy," recommendations for major defense contractors such as Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Japan Aircraft Manufacturing, and Fuji Heavy Industries.

Where does this leave America? With little bargaining power to use over Japan in military matters -- and little reason to use it. Japan is happier for having the United States as the big military power in the Pacific, so is the rest of Asia, and so is the United States. Every strategic and military trend in the area is favorable to American interests. There are no wars under way outside Indochina; most countries are becoming richer, freer, and more democratic. The only "threat" most Asian countries pose to the United States is through economic competition. Much of what is right in Asia is right because of the U.S. military presence, which has helped Japan to flourish peacefully and has kept everyone else from worrying about Japan. It would be shortsighted to upset this arrangement just to solve some trade problems. Trade problems are better dealt with on their own.

Copyright © 1989 by James Fallows. All rights reserved.

The Atlantic Monthly; April 1989; Japan: Let them Defend Themselves; Volume 264, No. 4; pages 34 - 38.